AUTHOR: Arpon Sarki, Assistant Professor, Harishchandrapur College, West Bengal, India.

Presently, India has surpassed China as being one of the largest populated countries in the world, boasting a staggering figure of over 1.43 billion individuals. However, it is disheartening to note that India lags behind in terms of female population, with tens of millions fewer women and girls than anticipated. Forecasts from the World Bank indicate that by 2031, there will be an additional 51 million men in the country, exacerbating an already troubling situation with 31 million more men than women. In the backdrop of India’s democratic society, gender inequality is universally acknowledged as a formidable hurdle in the path of establishing an egalitarian and righteous social structure. The inherent right to life, which serves as a bedrock of human life, is enshrined in Article 21 and has offered solace and nourishment to various other rights. Regrettably, the escalating number of missing women in India serves as a stark reminder that many women are being deprived of this fundamental right.

Amartya Sen and the afterword discourse: Amartya Kumar Sen, an Indian Nobel laureate, economist, and philosopher, presented the concept of “missing women” in the British Medical Journal in 1992. He estimated 100 million missing women, with 80% from India and China. Sen argued that women are hardier than men and survive better at all ages, including in utero. Social factors, such as the impact of men’s deaths in the last world war and more cigarette smoking and violent deaths among men, may explain the low female: male ratios in Asian and North African countries. He also discussed the comparative neglect of female health and nutrition, particularly during childhood. He also noted that despite a substantial reduction in female mortality, a new female disadvantage in natality has been introduced through sex-specific abortions. Similarly according to a study by Klasen and Wink (2002), close to 100 million women in Asia are missing (which includes having died because of discriminatory treatment in access to health and nutrition or through pure neglect). China and India each have about 42.6 million missing women. For example, the number of “missing women” in the early 1990s is larger than the combined deaths from all famines in the 20th century, also exceeding the combined death toll of the two world wars. Potential consequences of such imbalances, research suggests, include large numbers of frustrated men who cannot find partners, possible violence as well as a growing sex industry and sexual trafficking.

Discourse of estimate and reason: India’s demographic has a historically low sex ratio, with the lowest in the world throughout the 20th Century. This has led to the “missing females” phenomenon, with India having a 48.04% female population compared to a 51.96% male population. The country has slipped 28 places to rank 140th among 156 countries in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2021, becoming the third-worst performer in South Asia. India has closed 62.5% of its gender gap to date, ranking 112th among 153 countries in the Global Gender Gap Index 2020.

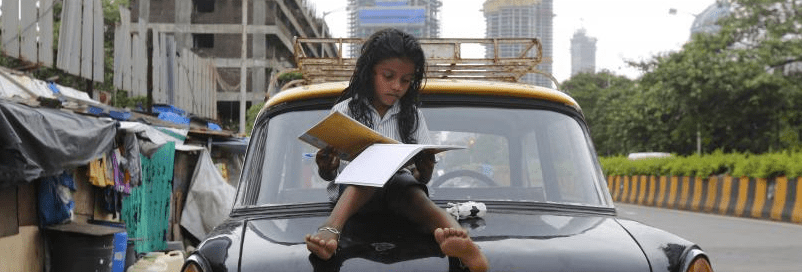

The Asia-Pacific Human Development Report published for UNDP in 2010 also claims that the countries of South Asia are characterized by large gender gaps and basic capabilities in terms of education, health, nutrition, and employment opportunities. As per the 2014 social institution and gender index, more than 90 million women have been missing around the world, 80% of these missing women are from India and the People’s Republic of China. India accounts for 45.8 million of the world’s 142.6 million “missing females” over the past 50 years, with the country and China making up the majority of such women globally. The 2018 Economic Survey revealed that India has 21 million “unwanted girls,” who are alive but likely disfavored by their parents. These girls receive less healthcare and schooling, with life-long effects on their well-being.

The distorted sex ratio in India is a result of prevalent gender inequality, discrimination against girls, and preference for sons. The country faces one of the highest female feticide and infanticide rates in the world, with about a million female fetuses aborted annually. Girls in India are traditionally considered less important and face a life-long process of discrimination, leading to a shorter lifespan. Social scientist Kamla Bhasin argues that the situation arises from a patriarchal and capitalist mindset prevalent in the country. India’s population sex ratios are abnormally higher due to prenatal sex selection favoring male births over female births. While there is a shift towards sex-selective abortion, the availability of sex-selective technology may increase the net proportions of girls “missing” rather than simply substituting for lower technology methods.

Breaking the conspiracy of silence: The problem of missing women appears to be a complex aggregate outcome of several individual and family-level behaviors. These behaviors emerge from interactions between economic circumstances, cultural traditions, and values, and evolved parenting biases and mating preferences. Challenging the ‘conspiracy of silence’ is therefore very tough mainly because people are very much less concerned about the issue of missing women and we found talking about this stigma at a minuscule level. In India, the educated are more likely to engage in illegal sex-selective abortions, to the extent that they can afford it, according to a 2011 study. Further, the Health Index released by the NITI Aayog in February shows that in recent years, the girl-to-boy sex ratio at birth has dropped in 17 out of 21 large States in India, including West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. Only in Bihar, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh has the sex ratio improved.

The Planning Commission of India has called the imbalance in the sex ratio “a silent demographic disaster in the making.” Various policies have been adopted to address these imbalances. For the problem of missing girls, governments have challenged the cultural preference for sons over daughters, prohibited sex-selective abortion, provided financial incentives and scholarship programs to families with daughters, and loosened fertility control policies. It is an important issue whether babies and pre-natal girls get equal treatment or not from their families. In some parts of the world, it seems sons are really getting preferred. In terms of medical care and attention, boys are getting much more than girls. In other words, women are missing because of the free natal state and the baby girl perhaps did not get the same attention, care, and medical treatment as received by the young boy and this is a scary thought. The solution, according to Sen is to improve female education improve female employment opportunities, and also improve the quality of norms that treat women in society in general Kerala does not have the same problem.

The challenge of gender is long-standing, probably going back millennia, so all stakeholders are collectively responsible for its resolution. Cultures do not stand still. Contemporary Indian culture is also a product of globalization and the economic needs of a fast-growing economy. Government programs in India that criminalize doctors, place pregnant women under surveillance, or offer women financial incentives not to abort female fetuses have all produced mixed results at best. Rather, the situation calls for a frank acknowledgment of the future problems and costs of sex-selective abortions, and more proactive measures, in both public and private sectors, to ensure that women are also benefiting from the country’s economic transformation India must confront the societal preference, even meta-preference for a son, which appears inoculated to development. The skewed sex ratio in favor of males led to the identification of “missing” women. But there may be a meta-preference manifesting itself in fertility-stopping rules contingent on the sex of the last child, which notionally creates “unwanted” girls, estimated at about 21 million. Consigning these odious categories to history soon should be society’s objective. It is worth worrying about balancing numbers i.e., sex ratio but it is equally important to have state policy that actually seeks to create the condition for meaningful life chances, beginning with those of girls and women.

*“The views expressed in the article are author’s personal and are not endorsed by the Global Policy Consortium (GPC) or assumed by their members”